Reporting from Orebro

BBC

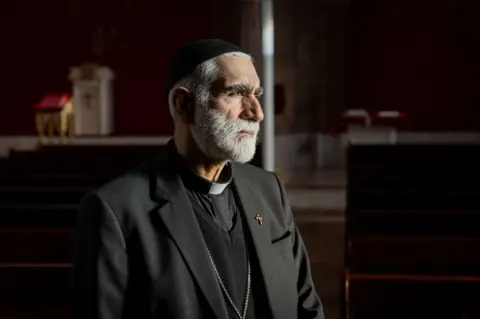

BBCIn the middle of a grand, high-ceilinged church in Orebro, Sweden, Jacob Kasselia, a Syrian orthodox priest, looked up towards the stained glass windows above him, then back down at his hands. He adjusted the gold cross hanging from his neck.

“The police say this man acted alone,” the priest said. “But this hate, it is coming from somewhere.”

A member of Kasselia’s congregation, 29-year-old Salim Iskef, was among those murdered in Orebro on Tuesday in Sweden’s first school shooting and the worst mass shooting in the country’s history. The gunman killed 10 students at an adult learning centre and then himself.

Among the dead are Syrians and Bosnians, according to residents and the embassies of those countries, but the police in Orebro have not given any details of the victims publicly.

Kasselia described Iskef as kind and thoughtful, keen to help other members of the community. He came to Sweden with his mother and sister, the priest said – refugees from Aleppo, where his father was killed in the war. Iskef was studying Swedish at the Risbergska school, the target of Tuesday’s attack.

“He was simply a good man,” the priest said. “He did not look for trouble. He showed only goodwill. He was a member of our community.”

The night after the attack, Kasselia sat with Iskef’s family to console them. Iskef was engaged and due to be married this summer. His fiancee Kareen Elia, 24, was “very badly affected”, the priest said, and was “going through a very difficult, very dark experience”.

At a memorial service in Orebro on Thursday night, Elia broke down in screams and tears and had to be carried out of the church.

In the days since the shooting, there has been a striking lack of information from the authorities. On Thursday night, police had still not confirmed the identity of the gunman – widely reported by Swedish media to be 35-year-old local Rickard Andersson – nor any details about his motive or the victims.

In a statement issued early on Tuesday, less than 24 hours after the attack, police said the shooter did not appear to be motivated by any ideology. On Thursday, Anna Bergkvist, who is leading the police investigation, appeared to walk the statement back.

“Why they said that, I cannot comment,” she told the BBC. “We are looking at different motives and we will declare it when we have it.”

Swedish police are usually cautious about naming suspects during an investigation, but the absence of official information has contributed to a feeling of fear and uncertainty among Orebro’s immigrant communities over the past few days.

“We are getting all our information from the media and I don’t know why,” said Nour Afram, 36, who was inside the Risbergska school when the attack began.

“We need more information,” she said. “We don’t know why he did it, why did he target this school? Was he sick or was it something else?”

Afram was waiting to go into class when she heard people screaming that there was a shooter – something so unbelievable to her she thought at first it was a prank.

“We started to run and then I heard the gunshots,” she said. “One at first, then tak tak tak – maybe ten shots. I was so scared I felt like my heart stopped in my chest.”

Afram, who immigrated from Syria to Orebro as a child, said she was afraid for the first time to send her three children to school in Sweden.

Zaki Aydin, a 50-year-old Syriac language teacher in Orebro, said he was afraid for the first time for his young students, who are mostly from the Middle East. “We are foreigners, we have to be careful now,” he said.

Aydin used to have the doors of his classroom and the church building open when he taught. “Now we are closing them,” he said. “And yesterday I asked someone to stand outside to prevent anyone we didn’t know already from coming in.”

One of the pupils at the school, 18-year-old Gabriel, said a “nightmare had come true” for Orebro.

“The problem is we have no motive, only speculation,” he said. “A lot of people my age are frightened to go to school, we feel like Sweden has become like America. The things you see on television have happened here.”

In the absence of any official news about the motive, all that the residents here in Orebro know is that the killer appears to have been a reclusive white Swedish man and that he targeted a school with a large immigrant student base.

Tomas Poletti Lundstrom, an academic researcher in racism at Uppsala University, who happens to live just a few minutes from the site of the attack and heard police helicopters fly over his home on Tuesday, said Orebro was facing a “deeply horrible time”.

“You can really sense it everywhere here, it is affecting everyone,” Lundstrom said. “We don’t know the motives of the shooter yet, but we are living in a very racist time and this is a school for a lot of immigrants.”

Attacks like the one at Risbergska were “the outcome of how our society looks at the moment, how our politicians talk, and how we talk about one another”, he said.

“The government and the main opposition support anti-immigrant policies and use anti-immigrant rhetoric,” he added. “This is what happens when politicians speak the way they are speaking.”

At the cordoned off entrance to Risbergska school early on Thursday morning, people were stopping by to leave flowers, light candles, or simply to stand and take in the scene. From the street, you can clearly see the front door through which the killer was filmed appearing to go from classroom to classroom with a rifle.

Among those who came alone and stood for a while by the collection of candles and flowers was the city’s mayor, John Johansson, who had made an official visit to the site the day before alongside the prime minister and the king and queen but stopped there again on his way to work on Thursday to pay his respects.

“I hope that the police will find conclusions soon,” Johansson said. “The city needs answers, our society needs answers, and the families of the victims need to know why this happened.”

But it was not time to “speculate or rush ahead”, he said. “We do not want to contribute to any false rumours, and so we hope the police will find answers as early as possible.”

Tony Estroem, a salesman from Eskilstuna, about 80km from Orebro, also stopped by the school on Thursday morning. “This kind of shooting, at a school, you read about it elsewhere but not in Sweden,” he said.

“It looks to be a Swedish guy, and perhaps that is better than if it had been an immigrant responsible,” he added. “Of course it is a terrible event either way, but we do not want to add more fuel to the fire.”

Police have given out some limited information about their investigation. They said that about 130 officers responded to the shooting in total, and that they were met by an “inferno” in the school. They said that they believe the gunman acted alone.

Family members, former school friends and neighbours have told Swedish media he had become a recluse in recent years and may have suffered with psychological issues.

There have been complaints about the handling of the case. The Bosnian ambassador Bojan Sosic, who also visited the site of the shooting, learned from residents that a Bosnian was among the dead.

“I find it odd, to say the least, that the police chooses to withhold information that pertains to foreign citizens from respective embassies,” he said.

Others, including members of the Syrian community, said they trusted the police were doing the right thing and only hoped to learn more soon. Kasselia, the Syrian Orthodox priest, said that the wider community “does not know what the police are thinking, but we trust that they have their own plan”.

Hundreds of people came to Kasselia’s church on Thursday night from the Syrian, Turkish, Iraqi and other migrant communities. A picture of Salim Iskef, one of the shooting’s victims, sat on an easel. Children from the congregation sung hymns. Iskef’s family, sitting in a pew near the front, were consumed by grief.

It is difficult to understand why these sorts of attacks happen even when the motive is known. Without it, it is even more confounding. A few hours before the memorial service began, Kasselia had been sitting in a pew in his empty church, trying to make sense of it.

“People die, of course. They become sick, they have some accident,” he said. “But this, how can we understand this? To be shot dead in a school. We could not dream of this. We cannot even describe it. Why?”

There was some comfort in hearing from the police that the gunman acted alone, Kasselia said. It left less anxiety of another attack.

“But this man had something in his heart, some kind of hate, that he gathered from somewhere,” the priest said. “We cannot say there are not others.”

Additional reporting by Phelan Chatterjee. Photographs by Joel Gunter.

Leave a Reply