New York

CNN

—

In early February, John Schwarz, a self-described “mindfulness and meditation facilitator,” proposed a 24-hour nationwide “economic blackout” of major chains on the last day of the month.

Schwarz urged people to forgo spending at Amazon, Walmart, and all other major retailers and fast-food companies for a day. He called on them to spend money only at small businesses and on essential needs.

“The system has been designed to exploit us,” said Schwarz, who goes by “TheOneCalledJai” on social media, in a video to his roughly 250,000 followers on Instagram and TikTok. “On February 28, we are going to remind them who really holds the power. For one day, we turn it off.”

Schwarz, 57, has no background in social or political organizing. Until early this year, he almost exclusively posted videos of himself offering inspirational messages and motivational tips sitting in his home, backyard and shopping mall parking lots.

He had low expectations for his boycott message gaining traction. “I thought maybe a handful of my followers would do it,” he told CNN in a phone interview this week.

Instead, Schwarz’s call rapidly spread online. His video has been shared more than 700,000 times on Instagram and viewed 8.5 million times. Celebrities such as Stephen King, Bette Midler and Mark Ruffalo have encouraged people to participate. Reporters wrote and aired TV pieces about the boycott, propelling it further.

The “economic blackout” effort is relatively uncoordinated and nebulous. Experts on consumer boycotts and corporate strategy are dubious that it will make a dent in the bottom lines of the massive companies it targets, let alone the vast US economy. Effective boycotts are typically well organized, make clear and specific demands and are focused on one company or issue.

But this boycott has gained strength online because it has captured visceral public anger with the American economy, corporations and politics.

“There’s the sense that a lot of people want to do something. Doing something in the American context has often meant using pocketbook politics,” said Lawrence Glickman, a historian at Cornell University and author of “Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in America.” “This a way of engaging in a form of collective action outside of the electoral arena that makes people feel some connection and sense of potential power.”

People online say they want to join the boycott for many different reasons. Some are commenting about high prices and the cost of living. Others are angry about the power of large corporations and billionaires such as Elon Musk. Some are pushing back against the Trump administration’s efforts to gut federal programs and fears about an autocracy in America. Yet others want to boycott companies rolling back their diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies.

Schwarz scrambled as a result of the response to create a group. He called it The People’s Union and describes it on its new website (that is frequently down) as a “movement created by the people, for the people to “(take) action against corporate control, political corruption, and the economic system.” He has raised around $70,000 in donations on a GoFundMe page that solicits funds for social campaigns, legal advocacy and other efforts. He has also called for more targeted boycotts in the coming weeks against specific companies, including Amazon and Walmart. (Walmart declined to comment to CNN. Amazon did not respond to comment.)

Although the response online appears to be strongest from the political left, Schwarz has no ideology that could be considered consistently progressive or conservative, at least along the traditional US political spectrum. He does not belong to either political party, but he supports Bernie Sanders. In recent posts, has advocated for the end of federal income tax, term limits in Congress, universal health care and price caps.

The boycott has “spread so well because people have just had enough and they’re fed up and they’re tired,” Schwarz said.

Schwarz’s boycott call has coincided with a more organized effort to punish retailers that have retreated on DEI, particularly Target.

Dozens of Fortune 500 companies have backtracked on their diversity programs in response to pressure from activists and right-wing legal groups, and, more recently, the Trump administration’s threats to investigate what it characterizes as “illegal DEI,” including potential criminal cases against companies.

Much of the anger has been directed toward Target. Target is under more heat than companies like Walmart, John Deere or Tractor Supply because it went further in its DEI efforts, and it has a more progressive base of customers.

Target was a leading advocate for DEI programs in the business world in the years after George Floyd was murdered by police in the company’s home city of Minneapolis in 2020. Target also spent years building a public reputation as a progressive employer on LGBTQ issues.

But days into the Trump presidency, Target announced it was eliminating hiring goals for minority employees, ending an executive committee focused on racial justice and making other changes to its diversity initiatives. Target said it remained committed to “creating a sense of belonging for our team, guests and communities” and also stressed the need for “staying in step with the evolving external landscape.”

Target’s retreat sparked anger from customers and boycott calls, particularly Black consumers.

Rev. Jamal Bryant of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church in Stonecrest, Georgia, has called for 100,000 people to begin a 40-day boycott of Target on March 5 to coincide with the start of Lent. Participants are encouraged to purchase products from Black-owned businesses during this period.

“We have witnessed a disturbing retreat from Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives by major corporations,” the petition says. “The greatest insult comes from Target.”

Target did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

There are signs that the blowback from Target’s move may be impacting the company.

Customer visits to Target, Walmart and Costco have slowed over the last four weeks, but they have dropped the most at Target, according to Placer.ai., which uses phone location data to track visits. The slowdown could also be attributed to weather, economic conditions and other variables, Placer.ai cautioned.

During the week of February 10, the latest week available, foot traffic to Target dropped 7.9% and 4.8% to Walmart. Foot traffic to Costco, which has stood by its DEI policies, increased 4.8%.

The data “shows a clear drop in traffic in late January into mid-February following the company’s step back from DEI,” Joseph Feldman, an analyst at Telsey Advisory Group, said in a note to clients this week.

Despite the recent slowdown at Target, boycotts tend to be short-lived and rarely do financial damage to companies.

“It’s very difficult to sustain anything longer than a few weeks,” said Young Hou, a marketing professor at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business who has studied consumer boycotts. Consumers are typically fickle and don’t want to disrupt their routines for extended stretches, he said. Boycotts can also spark a counterreaction, leading supporters of a company to mobilize and increase their spending, negating the impact.

A boycott campaign against Target may be hard to sustain because other chains that consumers might switch to like Walmart or Amazon have also rolled back DEI programs.

The most successful example of a boycott in recent years has come on the right.

In 2023, Bud Light’s parent company A-B InBev lost as much as $1.4 billion in sales because of right-wing backlash to Bud Light’s brief partnership with transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney.

Entertainer Kid Rock posted a video of himself shooting a stack of Bud Light cases. Other popular right-wing activists like Ben Shapiro and Candace Ownens and Republican politicans, including now-Vice President JD Vance and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, publicly supported the boycott. The brand also angered left-leaning customers because of its conciliatory response to right-wing attacks.

One of the key reasons the Bud Light boycott was successful was because it was very easy for customers to replace Bud Light with Coors Light or Miller Lite or another beer without much sacrifice.

Still, consumer boycotts and protests can raise public awareness about an issue, pressure companies to make changes or hurt their public reputations.

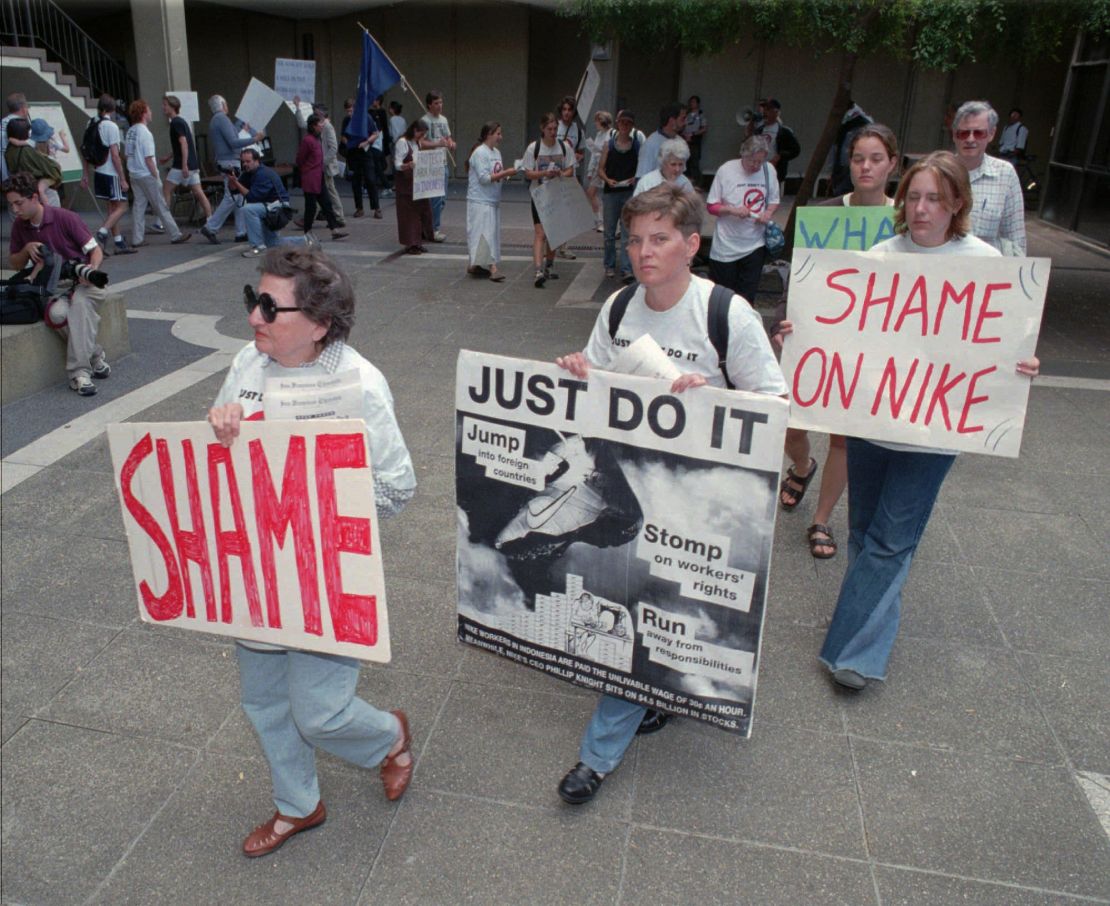

During the 1990s and 2000s, for example, protests on college campuses over Nike’s use of sweatshop labor forced the company to raise the minimum age for hiring new workers at shoe factories to 18 and allow human rights groups to inspect factory conditions in Asia. After the Parkland, Florida, school shooting in 2018, consumers and activists successfully pressured Delta, Avis, MetLife and other companies to sever ties with the National Rifle Association and end discounts to NRA members.

“The more specific the reason to boycott, usually the more effective those boycotts have a chance of being,” said Cornell University’s Glickman. “Boycotts rarely cripple incredibly powerful companies, but they can put them on the defensive.”